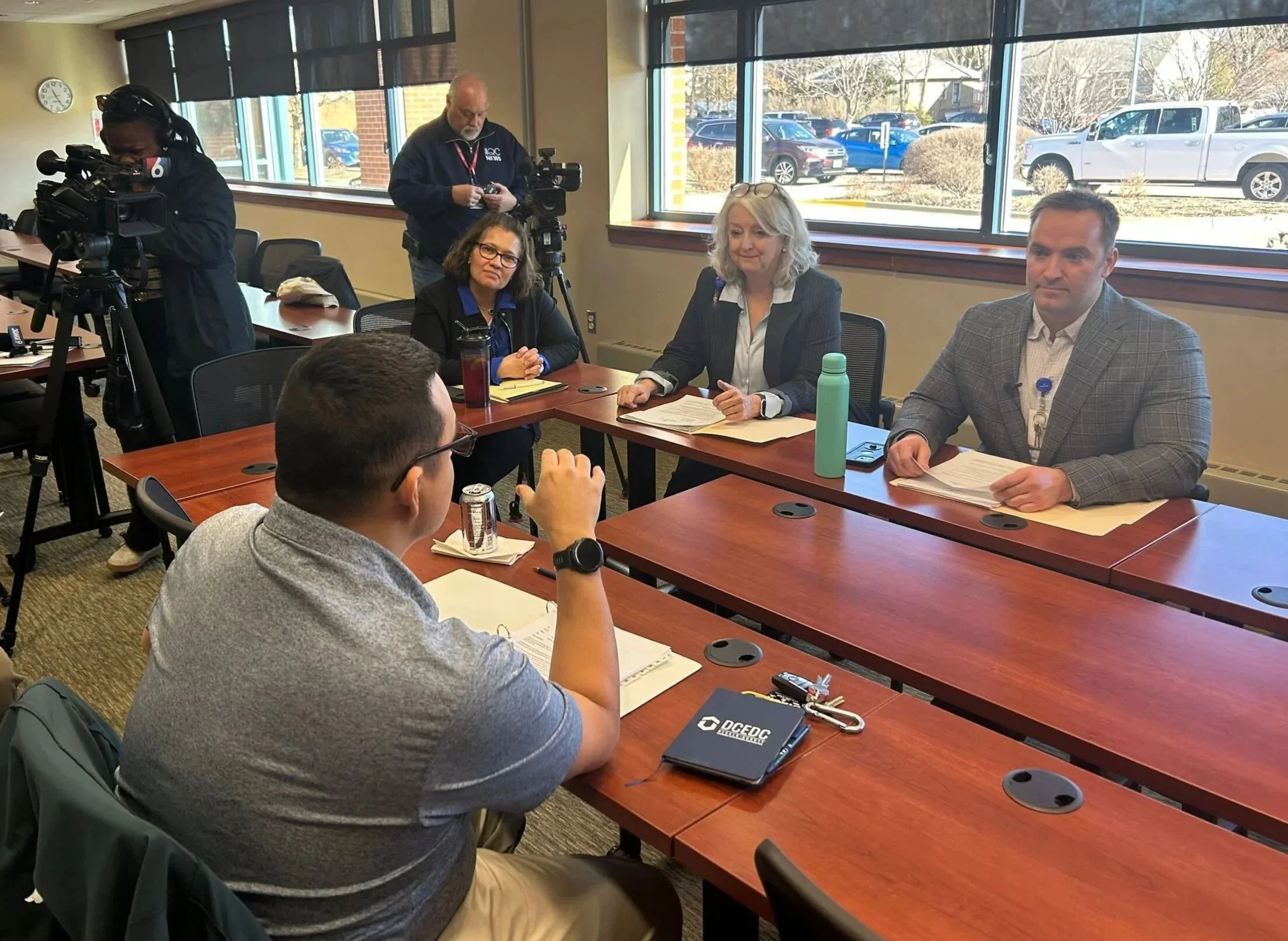

On January 12, Hammond-Henry Hospital hosted a press conference with State Representative Li Arellano to outline how gaps in state and federal funding are affecting rural hospitals. While Hammond-Henry serves a rural population, it is also designated as a critical access hospital, a classification intended to help ensure essential healthcare services remain available in remote communities.

Critical access hospitals are small, community-based facilities, typically located in rural areas, that provide vital medical services where alternatives are limited. There are more than 50 such hospitals across Illinois. Hospital leaders emphasized that funding challenges affecting these institutions extend beyond any single community.

State and federal funding programs, including 340B, are intended to support critical access and safety net hospitals. However, the 340B funding continues to see barriers. At the federal level, recent legislation has added or is seeking to add additional administrative requirements, making it more difficult and more costly for hospitals to access funds. Reliance on these funds helps to bring critically needed services that operate at a loss due to lack of economies of scale, recruitment/retention of talent, etc.

While lawmakers have cited $50 billion in aid for rural hospitals, Medicaid funding analysis suggests that those funds have been cut by three times that amount for rural communities over the last decade.

Critical access hospitals should receive 101 percent of allowable costs associated with Medicare. That reimbursement ends up being 98% of cost after sequestration. That margin is not enough to support the rise in costs that cannot be considered in the equation (example: advertising and other professional fees). The loss of coverage for our community means less payment and more patients transitioning to charity care.

Hammond-Henry Hospital CEO Wyatt Brieser said insurance reimbursement practices further complicate the issue. He noted that insurers often direct patients to larger regional facilities for ancillary services such as imaging, rehabilitation, or laboratory work, even when those services are available locally.

“Regarding ancillary services, unfortunately insurers are seeing that they can send a patient to Silvis to a specialized imaging center to receive an MRI,” Brieser said. “They see it as a cost savings. So, they force someone who lives in Atkinson, who sees their doctor here, and pays taxes here, to go elsewhere to receive the same quality care they could get at Hammond-Henry.”

Brieser added that transportation barriers can prevent patients from receiving care altogether. “If a patient doesn’t drive and relies on public transportation, and an insurer sends them to Rock Island for labs or another service, that patient may not receive the care they need,” he said. “All I’m asking for is patient choice.”

As a tax-supported institution, Hammond-Henry Hospital is a key community stakeholder. Brieser said long-term financial pressures could eventually force the hospital to consider reducing services, despite careful planning.

“Over the last 10 years, the hospital has planned for down years,” Brieser said. “We have reserves and a time horizon that allow us to weather difficult periods. But if performance indicators decline and we face ongoing barriers to providing care, along with rising cybersecurity, technology, and facility maintenance costs, we may be forced to make difficult decisions.”

He noted that operating costs continue to rise while payer reimbursements have not kept pace. “The cost of labor, materials, and services has increased,” Brieser said. “It’s frustrating to see situations where a $300 evaluation or diagnostic charge is reimbursed at, on average, 38% by insurers.” This is part of the disparity between healthcare and insurance that only hurts individuals who are left with self-pay costs that are inflated because payer contracts force charges to be higher for healthcare entities to remain viable at that reimbursement percentage.

Brieser said reductions in funding could have a cascading effect, particularly for specialty outpatient services. Programs such as pediatric rehabilitation and sporting event coverage that operates at a deficit, but is a significant need within the community, could be at risk if funding challenges persist.

“These services have survived because of our critical access status and the funding associated with it,” he said. “But it becomes increasingly difficult to continue them when that funding is no longer reliable.”

Hospital leadership also addressed concerns regarding the future of long-term care services. Hammond-Henry’s long-term care facility is a 38-bed center that, according to Brieser, has maintained a five-star rating for 14 consecutive years.

“We have one of the best long-term care facilities not just in Henry County, not just in Illinois, but in the nation,” Brieser said.

However, he noted that smaller facilities face financial challenges due to limited scale. The facility’s connection to the hospital remains a key advantage, allowing immediate access to emergency care, physical therapy, imaging, laboratory services, and infectious disease testing.

“If there’s an emergency, we can send residents down the hallway to the emergency room,” Brieser said. “Stand-alone facilities can’t do that. This model should be recognized by insurers as an example of how long-term care and hospitals can work together.”

Brieser emphasized the importance of maintaining local long-term care services for families and employees alike. “Our community relies on this facility,” he said. “Our staff knows the residents personally, and having quality care close to home allows families to remain connected to their loved ones.”

Hospital officials said discussions with lawmakers are ongoing as they continue to advocate for sustainable funding solutions that preserve access to healthcare services not just in Geneseo but also in rural Illinois.