By Claudia Loucks

Geneseo Current

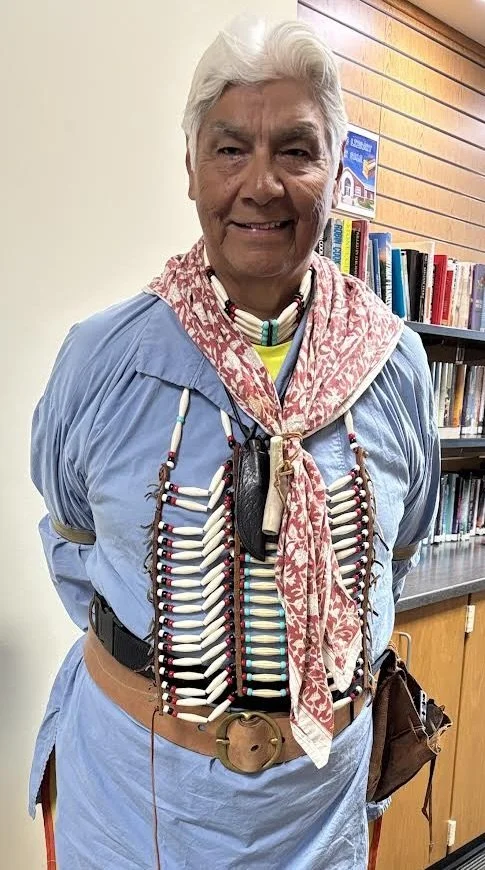

Native American Indian Rudy Vallejo will share his Native American culture through song and dance at 2 p.m. on Friday, Sept. 12, at the Geneseo Public Library. Weather permitting, Vallejo will put his tent up outside the library.

Vallejo did not grow up with the Kickapoo tribe, but often visited his family there. When he was nine years old, his grandfather gave him the Indian name, “Shoip-she-0wah-no,” which means “Vision of a Lion.” The name is of Potawatomi origin, as is his tribe. Kickapoo means “he who moves about. Potawatomi means “people of the fire.”

There are two other Kickapoo tribes in the U.S., the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas and the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma. There also are Kickapoo in Mexico, where Vallejo’s father was from. His mother’s family was of the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation from Kansas.

Vallejo’s maternal grandmother and grandfather (of Kickapoo descent) were sent to boarding schools designed to “take the Indian out of the Indian” and given the western names of “Susie and Frank.” Vallejo acknowledges the severe struggles encountered by Native children who were forced to abandon their culture and language and he thinks it’s important to “overcome those times and keep going.”

Information from the Geneseo Library included: “Sharing native culture and history during events such as the one at the Geneseo Library allows Native Americans opportunities to do that.”

Vallejo has been teaching the Eagle Dance to young and old for years in order to preserve and promote Native culture and history. He treasures the memories of his grandmother…” My grandmother inspired me to follow in her footsteps and carry on the tradition of dancing, and we need to teach our young people these values and traditions before we pass away and they are lost forever.”

The Eagle Dance is an honor dance traditionally performed in honor of the elders of the tribe. Vallejo explained that real feathers are used in the dance, but are received from the National Eagle Repository in Colorado. Because it is illegal to pick up Eagle feathers from the ground, native Americans can apply for them through the repository.

“There are 12 feathers on an eagle’s tail,” Vallejo explained. “The two middle feathers are the straightest. They are called the chief feathers. The two feathers on the outside are known as the dance feathers. These are the ones we wear on the dance roach when we perform the eagle dance.”

“The remaining eight feathers stand for what Native Americans, and all Americans, should be,” he added. “These traits are honesty, truth, majesty, strength, courage, wisdom, power and lastly, majesty.”

In order to prepare for the dance, Vallejo has to dress accordingly. On his head, he wears a head roach: which is a traditional headpiece fashioned of porcupine skin with red, white and blue feathers atop. And he must abstain from consuming alcohol. They must handle the eight eagle feathers with care so as not to drop them. In the event that they drop a feather on the floor, the drum would stop playing and a veteran would pick it up and return it to the dancer.

At one time, Vallejo said Indian tribes could trade eagle feathers for a horse. His grandfather taught him how to clean eagle feathers by dipping them twice in a river. Today, he still goes to the Mississippi River to clean the eagle feathers he owns.

Members of federally recognized tribes are allowed to own eagle feathers because of their great cultural and religious significance. However, even eligible Native Americans must get a permit to receive and own them. They are allowed to wear, use, inherit, and give eagle feathers to other Native Americans, but they cannot give them to non-Natives.